Free Progress Note Templates + Sanity-Saving Hacks

Psychotherapist, Kyrie Russ, writes in her newsletter: “Benjamin Franklin is famous for saying that the only certainties in life are death and taxes…and needing to write your progress notes.”

That last part was a joke, of course. (Or is it?)

Clinicians have many a bone to pick with progress notes. They’re time-consuming and not something many are trained to do right. Russ says it can be a source of self-doubt and anxiety — and who likes that?

But we’re here to help with tips, examples, and progress note templates to help you write better notes faster, so you can go home when your patients do.

What are progress notes?

If you're reading this, you likely know progress notes a little too well.

But they're more than a checklist; they're a medical necessity.

Think of yourself as the narrator in the ongoing story of your patient's physical and mental health. You're finding critical information and data to plot out the client's journey.

The history behind progress notes makes them even more fascinating.

Long before the electronic health record (or EHR— every clinicians least-favorite acronym), Dr. Larry Weed recognized a very real problem. As both a physician and researcher, he could see that fellow clinicians had no framework for recognizing problems.

This wasn't just a problem with clinical documentation. All around him, physicians were missing critical information because they didn't have a data-backed system.

That's why he created the problem-list, and soon after, the SOAP note template we know, love, and loathe today.

Progress note templates

Now, let’s go into a little more detail on how to write each type of progress note. Here are four templates you can download today.

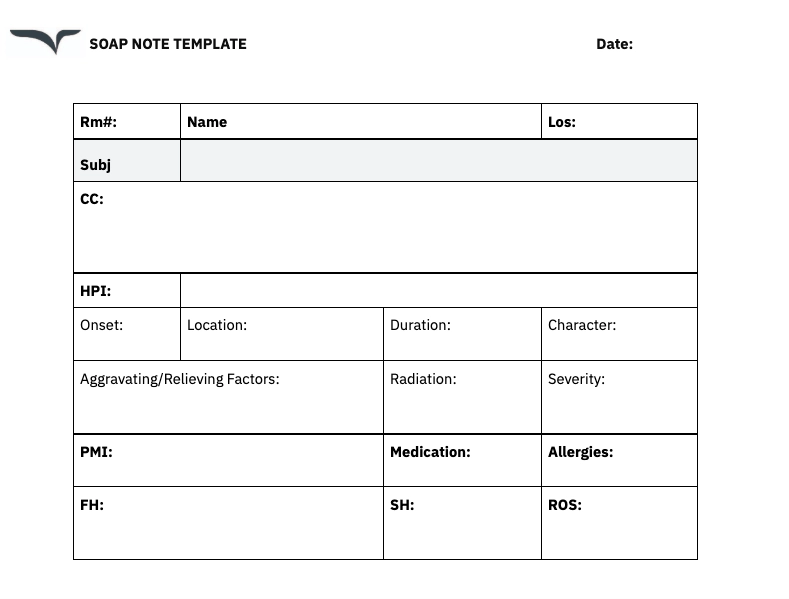

SOAP note template

How to write SOAP notes

You write a SOAP note with the chronological flow of your patient interactions.

You’ll start by documenting the issue your patient presents to you before moving on to your own assessment and recommendations.

Subjective: This section is for you to record patient-reported symptoms, concerns, or reason for the visit. Listen actively to your patient. You can include details like when their symptoms began, the severity of symptoms, and related triggers or medical history.

- Example: The patient says he has been feeling very tired and having headaches every morning.”

Objective: In this section, you’ll include measurable or observable data such as lab test results, vital signs, or physical observations. Remember to list observations down in the right order.

- Example: “The patient’s blood pressure measured 145/90. The patient was observed rubbing his temples during the exam.”

Assessment: You’ll then provide your clinical evaluation or diagnoses based on the subjective and objective data. You can record your clinical impressions if a formal diagnosis isn’t available yet.

- Example: “Stress-induced tension headaches. No signs of neurological deficits.”

Plan: Finally, lay out actionable next steps for treatment or follow-up care, including the need for referrals or additional tests. Be sure to include specific timelines for any action or goal.

- Example: “Recommend stress management techniques and a follow-up in two weeks. Prescribe acetaminophen for headache relief as needed.”

Prerounding note template

Download this template: In Portrait with 1pt/pg or Landscape with 3 pts/pg

How to write a prerounding note

In a prerounding note, you'll track basic patient details to monitor their hospital course and status. You’ll record key identifiers such as:

- Admitting diagnosis

- Pertinent past medical history

- Length of stay (LOS)

This helps provide context for their clinical status and treatment trajectory.

Subjective

Include overnight events, patient-reported symptoms, or updates from nursing staff. Focus on changes in pain, appetite, sleep, or new concerns.

Example:

- Improved appetite

- Intermittent nausea overnight

- No new complaints

Objective

Record measurable data, including vital signs, lab results, and imaging updates. Note significant changes or abnormalities.

Example:

- Vitals: HR 88, BP 120/80, RR 16, O2 sat 98% on RA

- Labs: WBC ↑ to 12.5 (prev. 10.2)

Assessment & Plan

Summarize your clinical impression and outline the next steps for management, including treatments, medication adjustments, and pending tests.

Example:

- Status: Stable overnight

- Plan: Continue IV fluids, advance diet as tolerated, repeat CBC tomorrow

To-Dos

List any follow-ups, consults, or documentation tasks before rounds.

Example:

- Follow up on pending blood cultures

- Check for PT/OT evaluation recommendations

- Keeping your prerounding note structured and concise ensures you're prepared to discuss each patient efficiently during rounds.

OT progress note template

How to write OT progress notes

Occupational therapy (OT) progress notes focus on helping patients perform meaningful activities in their daily lives. These notes track functional changes over time — think grooming, dressing, cooking, or handwriting.

Here’s a simple structure for an OT progress note:

Subjective:

Patient reports frustration with dressing tasks and fatigue during morning routines.

Objective:

Observed patient putting on a button-up shirt using adaptive technique. Required moderate verbal cueing and minimal physical assistance. Coordination improved from last session.

Assessment:

Progressing with fine motor skills. Still dependent for some dressing tasks but showing improved initiation and sequencing.

Plan:

Continue ADL-focused sessions 2x/week. Introduce new dressing aids and begin training next session.

Want to copy-paste this structure? Feel free. OT notes are all about functional impact—don’t overcomplicate it.

PT progress note template

Physical therapy (PT) notes are movement-focused. These notes are often a mix of pain management, strength, range of motion, and mobility improvements.

Here’s a quick example:

Subjective:

Patient reports decreased pain during walking and improved sleep since last session. Rates pain 3/10 (down from 6/10).

Objective:

Gait analysis: mild limp remains but stride length improved. Left hamstring strength tested 4/5 (previously 3/5). Completed all exercises with good form and no rest breaks.

Assessment:

Patient demonstrating functional gains in strength and endurance. Mild compensations still present but improving.

Plan:

Advance therapeutic exercises. Introduce single-leg balance work. Continue 3x/week sessions and reassess ROM next week.

How to write progress notes

Let's break down how to write the other popular note types: DAP and BIRP.

How to write DAP notes

DAP notes are more concise than SOAP notes, focusing on information that can be immediately analyzed and acted upon. For this reason, you’ll start DAP notes with data and observations before clearly interpreting that data into a plan of action.

Data: You’ll record measurable data such as lab test results, vital signs, or physical observations. Unlike SOAP notes, refrain from adding subjective input or narrative details.

- Example: “Patient reports difficulty sleeping (2-3 hours per night) and loss of appetite after a recent car accident. Pulse recorded at 102 bpm during the session.”

Assessment: In this section, you’ll summarize your clinical evaluation based on the data presented above.

- Example: Patient is presenting with symptoms consistent with acute stress disorder following a traumatic event.”

Plan: Finally, you’ll clearly outline your immediate next steps for a patient’s treatment or follow-up care.

- Example: “Provided grounding exercises to reduce distress and demonstrated techniques during the session. Referred to trauma counselor for evaluation within one week.”

How to write BIRP notes

Remember, BIRP notes are all about tracking patient behavior and responses rather than data. Here’s how you can approach writing them.

Behavior: Describe any behavior or expressions you observe during a session. Focus on behavior relevant to why your patient is seeing you during this session.

- Example: “Patient appeared withdrawn, avoided eye contact, and spoke in a soft voice when discussing recent family conflicts.”

Intervention: Document the techniques used during the session to help manage symptoms.

- Example: “Facilitated discussion on family communication strategies and introduced role-playing exercises.”

Response: Explain how the patient reacted to the intervention. You can note any changes in their behavior, mood, or engagement throughout the session.

- Example: “Patient engaged in role-playing exercises and expressed feeling more confident about addressing conflicts.”

Plan: Outline your next steps in the treatment process.

- Example: “Focus on practicing communication strategies during next session. Schedule family counseling session within two weeks.

Why do progress notes matter?

Skipping out on progress notes or doing them wrong can put your practice in jeopardy.

They’re there for a reason: To give care teams an accurate log of a patient’s clinical interactions.

HIPAA compliance

As a clinician, your previous notes prove you’ve done your job right. Compliance is something you wouldn’t have to worry about. It becomes a legally binding document that helps you build a case in court too.

For patients, progress notes play an equally important role. It tells the full story of what’s going on during treatment—which insurers need to approve reimbursements.

And beyond the legality of it all, clinicians who write progress notes do better work.

We’re not just saying that to put documentation on a pedestal. Beth Rontal, writes in Psychotherapy Networker about how she found value in reviewing therapy progress notes with her patient every time the patient got discouraged.

“As she absorbed the notes, Kerry realized the binge-eating part of her was keeping at bay the anger that hadn’t been safe to express as a child. Part of her wanted to express that anger now, which was a valuable insight,” Rontal shares.

The reality is that everything clicks because previous notes help patients and clinicians get the full picture.

Nurses stepping in on a case can immediately understand next steps. Therapists or specialists can quickly decide on treatment plans that are working—or not—without delays. And patients become a lot easier to persuade if they can see progress for themselves, step into your world, and make their journey easier to understand.

What to avoid when writing progress notes

That said, creating progress notes just to check a box adds little value.

Poorly written progress notes slow everyone down. Here are a few common pitfalls that defeat the purpose of progress notes:

- Notes that are too vague or overly detailed: A vague note like, “Patient is feeling a little ‘off’ lately; follow-up in two weeks,” doesn’t give care teams insight into the actual presenting problem. On the other hand, you don’t want to go so into detail that you clutter your EHR system with irrelevant observations.

- Not tying any assessment action back to a patient concerns: A note that reads, “Patient is advised to increase physical activity,” provides little context into why or how this action will reach a particular goal or objective in your treatment plan.

- Inconsistent formats that confuse or delay care decisions: Switching between different writing formats or following the wrong structure will disrupt the flow of a progress note and make it harder for care team members to understand key takeaways. Don’t worry, we’ll learn more about these formats as you keep reading!

Progress note tips & tricks

The Rontal article we talked about has a bold name.

It’s called “I’d rather clean the toilet than write progress notes.”

Well, to be fair, the rest of the title said: “Making peace with an essential task.”

Her point is: It’s never going to be the most fun doing it. In fact, the question that prompts the article talks about progress notes being the worst part of their job. But Rontal adds that there are ways to make the process much more seamless.

And because we don’t want you to feel like you’d rather clean toilets, we’ll share a few best practices to save you time and effort.

- Use a progress note template: There’s no reason to start your notes from scratch or think about formatting every single time. Save one of our templates above, tailor each section it to your session, and build from there. Your electronic health record (EHR) system should also give you access to customizable templates.

- Keep your progress report simple: You don’t need much to get your point across. Stick to the main points for each section and avoid frills like big words, complex jargon, or long paragraphs and sentences. Imagine what would be easiest to scan in a few seconds or on the go, and write with that urgency in mind.

- Context vs. Overexplaining: Context is important — but focus takes the cake. Not every detail needs to be documented, just the ones that tie directly to the patient’s presenting problem or your treatment goals.

- Be consistent and logical: Once you’ve selected a format for your progress note, stick to it. Follow the requirements of each section carefully and don’t switch between different formats halfway through or make your own little tweaks. These formats are there for a reason, and any changes will throw the rest of your team off.

- Stay factual and professional: Progress notes are legal documents, so keep them unbiased and centered on the goal of your session. Don’t insert any personal opinions, theoretical assumptions, or any sort of judgment.

- Use AI medical scribes: Transcription software and medical AI scribes can make the process faster and more accurate by writing notes for you while you go about your session. Tools like Freed can help you automatically format dictations into structured progress notes.

- Don’t wait too long to get your notes done: As tempting as it is to wait until the end of the week to write all your progress notes, the best time to do it is still as soon as you can. Knocking out a stack of notes in a rush is overwhelming for anyone — even with transcription software or AI. Thank yourself later by breaking your workload and giving your weekend self more time to relax.

A hopeful reminder to take with you

Your note-taking process should work for you, not the other way around.

Choose the format that makes your life easier, and take advantage of the templates and tools that give you time back — a few minutes a note can go a long way.

Another helpful tip? Give yourself credit where it's due, and maybe even a reward. “One therapist I know gives herself three M&M’s after every note. Another hits the gym for a reward,” Rontal writes.

What about you?

Freed is the most clinician-focused company in the world. Try our AI scribe for free.

Free Progress Note Templates + Sanity-Saving Hacks

Table of Contents

Psychotherapist, Kyrie Russ, writes in her newsletter: “Benjamin Franklin is famous for saying that the only certainties in life are death and taxes…and needing to write your progress notes.”

That last part was a joke, of course. (Or is it?)

Clinicians have many a bone to pick with progress notes. They’re time-consuming and not something many are trained to do right. Russ says it can be a source of self-doubt and anxiety — and who likes that?

But we’re here to help with tips, examples, and progress note templates to help you write better notes faster, so you can go home when your patients do.

What are progress notes?

If you're reading this, you likely know progress notes a little too well.

But they're more than a checklist; they're a medical necessity.

Think of yourself as the narrator in the ongoing story of your patient's physical and mental health. You're finding critical information and data to plot out the client's journey.

The history behind progress notes makes them even more fascinating.

Long before the electronic health record (or EHR— every clinicians least-favorite acronym), Dr. Larry Weed recognized a very real problem. As both a physician and researcher, he could see that fellow clinicians had no framework for recognizing problems.

This wasn't just a problem with clinical documentation. All around him, physicians were missing critical information because they didn't have a data-backed system.

That's why he created the problem-list, and soon after, the SOAP note template we know, love, and loathe today.

Progress note templates

Now, let’s go into a little more detail on how to write each type of progress note. Here are four templates you can download today.

SOAP note template

How to write SOAP notes

You write a SOAP note with the chronological flow of your patient interactions.

You’ll start by documenting the issue your patient presents to you before moving on to your own assessment and recommendations.

Subjective: This section is for you to record patient-reported symptoms, concerns, or reason for the visit. Listen actively to your patient. You can include details like when their symptoms began, the severity of symptoms, and related triggers or medical history.

- Example: The patient says he has been feeling very tired and having headaches every morning.”

Objective: In this section, you’ll include measurable or observable data such as lab test results, vital signs, or physical observations. Remember to list observations down in the right order.

- Example: “The patient’s blood pressure measured 145/90. The patient was observed rubbing his temples during the exam.”

Assessment: You’ll then provide your clinical evaluation or diagnoses based on the subjective and objective data. You can record your clinical impressions if a formal diagnosis isn’t available yet.

- Example: “Stress-induced tension headaches. No signs of neurological deficits.”

Plan: Finally, lay out actionable next steps for treatment or follow-up care, including the need for referrals or additional tests. Be sure to include specific timelines for any action or goal.

- Example: “Recommend stress management techniques and a follow-up in two weeks. Prescribe acetaminophen for headache relief as needed.”

Prerounding note template

Download this template: In Portrait with 1pt/pg or Landscape with 3 pts/pg

How to write a prerounding note

In a prerounding note, you'll track basic patient details to monitor their hospital course and status. You’ll record key identifiers such as:

- Admitting diagnosis

- Pertinent past medical history

- Length of stay (LOS)

This helps provide context for their clinical status and treatment trajectory.

Subjective

Include overnight events, patient-reported symptoms, or updates from nursing staff. Focus on changes in pain, appetite, sleep, or new concerns.

Example:

- Improved appetite

- Intermittent nausea overnight

- No new complaints

Objective

Record measurable data, including vital signs, lab results, and imaging updates. Note significant changes or abnormalities.

Example:

- Vitals: HR 88, BP 120/80, RR 16, O2 sat 98% on RA

- Labs: WBC ↑ to 12.5 (prev. 10.2)

Assessment & Plan

Summarize your clinical impression and outline the next steps for management, including treatments, medication adjustments, and pending tests.

Example:

- Status: Stable overnight

- Plan: Continue IV fluids, advance diet as tolerated, repeat CBC tomorrow

To-Dos

List any follow-ups, consults, or documentation tasks before rounds.

Example:

- Follow up on pending blood cultures

- Check for PT/OT evaluation recommendations

- Keeping your prerounding note structured and concise ensures you're prepared to discuss each patient efficiently during rounds.

OT progress note template

How to write OT progress notes

Occupational therapy (OT) progress notes focus on helping patients perform meaningful activities in their daily lives. These notes track functional changes over time — think grooming, dressing, cooking, or handwriting.

Here’s a simple structure for an OT progress note:

Subjective:

Patient reports frustration with dressing tasks and fatigue during morning routines.

Objective:

Observed patient putting on a button-up shirt using adaptive technique. Required moderate verbal cueing and minimal physical assistance. Coordination improved from last session.

Assessment:

Progressing with fine motor skills. Still dependent for some dressing tasks but showing improved initiation and sequencing.

Plan:

Continue ADL-focused sessions 2x/week. Introduce new dressing aids and begin training next session.

Want to copy-paste this structure? Feel free. OT notes are all about functional impact—don’t overcomplicate it.

PT progress note template

Physical therapy (PT) notes are movement-focused. These notes are often a mix of pain management, strength, range of motion, and mobility improvements.

Here’s a quick example:

Subjective:

Patient reports decreased pain during walking and improved sleep since last session. Rates pain 3/10 (down from 6/10).

Objective:

Gait analysis: mild limp remains but stride length improved. Left hamstring strength tested 4/5 (previously 3/5). Completed all exercises with good form and no rest breaks.

Assessment:

Patient demonstrating functional gains in strength and endurance. Mild compensations still present but improving.

Plan:

Advance therapeutic exercises. Introduce single-leg balance work. Continue 3x/week sessions and reassess ROM next week.

How to write progress notes

Let's break down how to write the other popular note types: DAP and BIRP.

How to write DAP notes

DAP notes are more concise than SOAP notes, focusing on information that can be immediately analyzed and acted upon. For this reason, you’ll start DAP notes with data and observations before clearly interpreting that data into a plan of action.

Data: You’ll record measurable data such as lab test results, vital signs, or physical observations. Unlike SOAP notes, refrain from adding subjective input or narrative details.

- Example: “Patient reports difficulty sleeping (2-3 hours per night) and loss of appetite after a recent car accident. Pulse recorded at 102 bpm during the session.”

Assessment: In this section, you’ll summarize your clinical evaluation based on the data presented above.

- Example: Patient is presenting with symptoms consistent with acute stress disorder following a traumatic event.”

Plan: Finally, you’ll clearly outline your immediate next steps for a patient’s treatment or follow-up care.

- Example: “Provided grounding exercises to reduce distress and demonstrated techniques during the session. Referred to trauma counselor for evaluation within one week.”

How to write BIRP notes

Remember, BIRP notes are all about tracking patient behavior and responses rather than data. Here’s how you can approach writing them.

Behavior: Describe any behavior or expressions you observe during a session. Focus on behavior relevant to why your patient is seeing you during this session.

- Example: “Patient appeared withdrawn, avoided eye contact, and spoke in a soft voice when discussing recent family conflicts.”

Intervention: Document the techniques used during the session to help manage symptoms.

- Example: “Facilitated discussion on family communication strategies and introduced role-playing exercises.”

Response: Explain how the patient reacted to the intervention. You can note any changes in their behavior, mood, or engagement throughout the session.

- Example: “Patient engaged in role-playing exercises and expressed feeling more confident about addressing conflicts.”

Plan: Outline your next steps in the treatment process.

- Example: “Focus on practicing communication strategies during next session. Schedule family counseling session within two weeks.

Why do progress notes matter?

Skipping out on progress notes or doing them wrong can put your practice in jeopardy.

They’re there for a reason: To give care teams an accurate log of a patient’s clinical interactions.

HIPAA compliance

As a clinician, your previous notes prove you’ve done your job right. Compliance is something you wouldn’t have to worry about. It becomes a legally binding document that helps you build a case in court too.

For patients, progress notes play an equally important role. It tells the full story of what’s going on during treatment—which insurers need to approve reimbursements.

And beyond the legality of it all, clinicians who write progress notes do better work.

We’re not just saying that to put documentation on a pedestal. Beth Rontal, writes in Psychotherapy Networker about how she found value in reviewing therapy progress notes with her patient every time the patient got discouraged.

“As she absorbed the notes, Kerry realized the binge-eating part of her was keeping at bay the anger that hadn’t been safe to express as a child. Part of her wanted to express that anger now, which was a valuable insight,” Rontal shares.

The reality is that everything clicks because previous notes help patients and clinicians get the full picture.

Nurses stepping in on a case can immediately understand next steps. Therapists or specialists can quickly decide on treatment plans that are working—or not—without delays. And patients become a lot easier to persuade if they can see progress for themselves, step into your world, and make their journey easier to understand.

What to avoid when writing progress notes

That said, creating progress notes just to check a box adds little value.

Poorly written progress notes slow everyone down. Here are a few common pitfalls that defeat the purpose of progress notes:

- Notes that are too vague or overly detailed: A vague note like, “Patient is feeling a little ‘off’ lately; follow-up in two weeks,” doesn’t give care teams insight into the actual presenting problem. On the other hand, you don’t want to go so into detail that you clutter your EHR system with irrelevant observations.

- Not tying any assessment action back to a patient concerns: A note that reads, “Patient is advised to increase physical activity,” provides little context into why or how this action will reach a particular goal or objective in your treatment plan.

- Inconsistent formats that confuse or delay care decisions: Switching between different writing formats or following the wrong structure will disrupt the flow of a progress note and make it harder for care team members to understand key takeaways. Don’t worry, we’ll learn more about these formats as you keep reading!

Progress note tips & tricks

The Rontal article we talked about has a bold name.

It’s called “I’d rather clean the toilet than write progress notes.”

Well, to be fair, the rest of the title said: “Making peace with an essential task.”

Her point is: It’s never going to be the most fun doing it. In fact, the question that prompts the article talks about progress notes being the worst part of their job. But Rontal adds that there are ways to make the process much more seamless.

And because we don’t want you to feel like you’d rather clean toilets, we’ll share a few best practices to save you time and effort.

- Use a progress note template: There’s no reason to start your notes from scratch or think about formatting every single time. Save one of our templates above, tailor each section it to your session, and build from there. Your electronic health record (EHR) system should also give you access to customizable templates.

- Keep your progress report simple: You don’t need much to get your point across. Stick to the main points for each section and avoid frills like big words, complex jargon, or long paragraphs and sentences. Imagine what would be easiest to scan in a few seconds or on the go, and write with that urgency in mind.

- Context vs. Overexplaining: Context is important — but focus takes the cake. Not every detail needs to be documented, just the ones that tie directly to the patient’s presenting problem or your treatment goals.

- Be consistent and logical: Once you’ve selected a format for your progress note, stick to it. Follow the requirements of each section carefully and don’t switch between different formats halfway through or make your own little tweaks. These formats are there for a reason, and any changes will throw the rest of your team off.

- Stay factual and professional: Progress notes are legal documents, so keep them unbiased and centered on the goal of your session. Don’t insert any personal opinions, theoretical assumptions, or any sort of judgment.

- Use AI medical scribes: Transcription software and medical AI scribes can make the process faster and more accurate by writing notes for you while you go about your session. Tools like Freed can help you automatically format dictations into structured progress notes.

- Don’t wait too long to get your notes done: As tempting as it is to wait until the end of the week to write all your progress notes, the best time to do it is still as soon as you can. Knocking out a stack of notes in a rush is overwhelming for anyone — even with transcription software or AI. Thank yourself later by breaking your workload and giving your weekend self more time to relax.

A hopeful reminder to take with you

Your note-taking process should work for you, not the other way around.

Choose the format that makes your life easier, and take advantage of the templates and tools that give you time back — a few minutes a note can go a long way.

Another helpful tip? Give yourself credit where it's due, and maybe even a reward. “One therapist I know gives herself three M&M’s after every note. Another hits the gym for a reward,” Rontal writes.

What about you?

Freed is the most clinician-focused company in the world. Try our AI scribe for free.

FAQs

Frequently asked questions from clinicians and medical practitioners.

What is the most common format for patient progress notes?

What not to include in patient notes

What is an example of a progress note?

What are the four sections of a progress note?

Related content

.avif)